Aboriginal peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. The descriptors “Indian” and “Eskimo” are falling into disuse. Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are the earliest archaeological sites of human habitation in Canada. Hundreds of Aboriginal nations evolved trade, spiritual and social hierarchies. The Métis culture of mixed blood originated in the mid-17th century when First Nation and native Inuit married European settlers. The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during that early period. Various laws, treaties, and legislation have been enacted between European immigrants and First Nations across Canada. Aboriginal Right to Self-Government provides opportunity to manage historical, cultural, political, health care and economic control aspects within first people’s communities.

Although not without conflict, European/Canadian early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful, compared to the experience of native peoples in the United States. Combined with relatively late economic development in many regions, this peaceful history has allowed Canadian Indigenous peoples to have a relatively strong influence on the national culture while preserving their own identity. There are currently over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands encompassing 1,172,790 people spread across Canada with distinctive Aboriginal cultures, languages, art, and music.

2.10.1 Formative Period

Among the First Nations peoples, there are eight unique stories of creation and their adaptations. These are the earth diver, world parent, emergence, conflict, robbery, rebirth of corpse, two creators and their contests, and the brother myth. Canadian Aboriginal civilizations established permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilisations had long faded by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are discovered through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with this period recorded in historical accounts of the time. When the Europeans arrived, natives of North America were semi-nomadic tribes of hunter-gatherers; others were sedentary and agricultural civilisations. New tribes or confederations formed in response to European colonisation.

The Old Copper Complex ancient societies dates from 3000 BC to 500 BC; it is a manifestation of the Woodland Culture, but is pre-pottery. Found in the northern Great Lakes regions, they extracted copper from local glacial deposits and used it to manufacture tools and implements. The Woodland Cultural period dates from 1000 BC — 1000 AD and is associated with Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime regions. The introduction of pottery distinguishes the Woodland culture from the archaic stage. Laurentian people of southern Ontario manufactured the oldest pottery excavated in Canada. They created pointed-bottom beakers they decorated by a cord marking technique that involved impressing tooth implements into wet clay. Woodland technology includes items such as beaver incisor knives, bangles, and chisels. Sedentary agricultural lifeways resulted in a population increase engendered by a diet of squash, corn, and bean crops.

The Norton tradition is an archaeological culture that developed in the Western Arctic along the Alaskan shore of the Bering Strait from 1000 BC and lasted through about 900 AD. The Norton people used flake-stone tools like their predecessors the Artics, but they were more marine-oriented and brought new technologies such as oil-burning lamps and clay vessels into use. They hunted caribou and smaller mammals as well as salmon and larger marine mammals. Village sites that contained substantial dwellings showed permanent settlement. The Hopewell tradition is the term used to describe common aspects of the Aboriginal culture that flourished along rivers in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States from 300 BC to 500 AD. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a dispersed set of related populations connected by a common network of trade routes, known as the Hopewell Exchange System. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell exchange system ran from the Southeastern United States into the southeastern Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Local expression of the Hopewellian peoples in Canada includes the Point Peninsula Complex, Saugeen Complex, and Laurel Complex.

2.10.2 Classic and Post-Classic Period

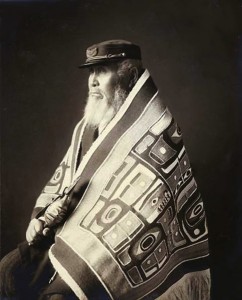

First Nations had settled across Canada by 500 BC – 1000 AD. Hundreds of tribes had developed, each with its own culture, customs, legends, and character. In the northwest were the Athapaskan speaking peoples, Slavey, Tli Cho, Tutchone speaking peoples and Tlingit. Along the Pacific coast were the Haida, Salish, Kwakiutl, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nisga’a and Gitxsan. In the plains were the Blackfoot, Kainai, Sarcee and Northern Peigan. In the northern woodlands were the Cree and Chipewyan. Around the Great Lakes were the Anishinaabe, Algonquin, Micmac, Iroquois and Wyandot. Along the Atlantic coast were the Beothuk, Maliseet, Innu, Abenaki and Micmac.

The Blackfoot Indians —also known as the Blackfeet Indians— reside in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The name ‘Blackfoot’ came from the colour of the peoples’ leather footwear, known as moccasins. They had come from the upper Northeastern area of the USA. The Blackfoot started as woodland Indians but as they made their way over to the Plains, they adapted to new ways of life and became accustomed to the land. They knew the new lands that they travelled to very well and established themselves as Plains Indians in the late 1700s, earning themselves the name “The Lords of the Plains.”

The Sḵwxwú7mesh (Sqamish) history is a series of past events, both passed on through oral tradition and recent history, of the Sḵwxwú7mesh indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Prior to colonisation, they recorded their history through oral tradition as a way to transmit stories, law, and knowledge across generations. It was a respectable responsibility of knowledgeable elders to pass historical knowledge to the next generation. People lived and prospered for thousands of years until the Great Flood. In another story, after the Flood, they would repopulate from the villages of Schenks and Chekwelp, located at Gibsons. When the water lines receded, the first Sḵwxwú7mesh came to be. The first man, named Tsekánchten, built his long house in the village, and later on another man named Xelálten, appeared on his long house roof and sent by the Creator, or in the Sḵwxwú7mesh language keke7nex siyam. He called this man his brother. It was from these two men that the population began to rise and the Sḵwxwú7mesh spread back through their territory.

The Assiniboine were close allies and trading partners of the Cree, engaging in wars against the Gros Ventres alongside them, and later fighting the Blackfeet. A Plains people, they went no further north than the North Saskatchewan River and purchased a great deal of European trade goods from the Hudson’s Bay Company through Cree middlemen. The life style of this group was semi-nomadic, and they would follow the herds of bison during the warmer months. They worked with the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes, and that factor is attached to their life style.

In the earliest oral history, the Algonquins were from the Atlantic coast. Together with other Anicinàpek, they arrived at the “First Stopping Place” near Montreal. While the other Anicinàpe peoples continued their journey up the Saint Lawrence River, the Algonquins settled along the Kitcisìpi (Ottawa River), an important highway for commerce, cultural exchange, and transportation from time immemorial.

Lawrence River, the Algonquins settled along the Kitcisìpi (Ottawa River), an important highway for commerce, cultural exchange, and transportation from time immemorial.

According to their tradition, and from recordings in wiigwaasabak (birch bark scrolls), Ojibwe came from the eastern areas of North America, or Turtle Island, and from along the east coast. They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast.

According to the oral history, seven great miigis (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the Waabanakiing to teach the peoples of the mide way of life. One of the seven great miigis beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the Waabanakiing when the people were in its presence. The six great miigis beings remained to teach while the one returned into the ocean. The six great miigis beings then established doodem (clans) for the peoples in the east. Of these doodem, the five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan’aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose), then these six miigis beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh miigis being stayed, it would have established the Thunderbird doodem.

The Nuu-chah-nulth are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The term ‘Nuu-chah-nulth’ is used to describe fifteen separate but related First Nations, such as the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations, Ehattesaht First Nation and Hesquiaht First Nation whose traditional home is in the Pacific Northwest on the west coast of Vancouver Island. In pre-contact and early post-contact times, the number of nations was much greater, but smallpox and other consequences of contact resulted in the disappearance of groups, and the absorption of others into neighbouring groups. The Nuu-chah-nulth are relations of the Kwakwaka’wakw, the Haisla, and the Ditidaht. The Nuu-chah-nulth language is part of the Wakashan language group.

A 1999 discovery of the body of Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi has provided archaeologists with significant information on indigenous tribal life prior to extensive European contact. Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi (meaning Long Ago Person Found in Southern Tutchone), or Canadian Ice Man, is a naturally mummified body found in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in British Columbia. Radiocarbon dating of artefacts found with the body placed the age of the find between 1450 AD and 1700 AD. Genetic testing has shown he was a member of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. An examination of the contents of his digestive system provided details about what he had eaten. He was found with a number of artefacts, including a robe made from about 95 gopher or squirrel skins sewn together with sinew, a woven hat, a walking stick, an iron bladed knife, a hand tool of unknown purpose, and an atlatl and dart. Archaeologists studied preserved samples, and cremated the remainder of Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi’s remains. Local clans are considering a memorial potlatch to honour Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi.

Southern Tutchone), or Canadian Ice Man, is a naturally mummified body found in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in British Columbia. Radiocarbon dating of artefacts found with the body placed the age of the find between 1450 AD and 1700 AD. Genetic testing has shown he was a member of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. An examination of the contents of his digestive system provided details about what he had eaten. He was found with a number of artefacts, including a robe made from about 95 gopher or squirrel skins sewn together with sinew, a woven hat, a walking stick, an iron bladed knife, a hand tool of unknown purpose, and an atlatl and dart. Archaeologists studied preserved samples, and cremated the remainder of Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi’s remains. Local clans are considering a memorial potlatch to honour Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi.

The Icelandic Sagas documents the earliest known European explorations in Canada and the attempted Norse colonisation of the Americas. According to sagas, the first European to see Canada was Bjarni Herjólfsson in the summer of 985 or 986 due to an accidental re-routeing from Iceland to Greenland because of strong winds. Leif Ericson sailed with a crew of 35 to investigate Bjarni’s discovery around the year 1000. Leif landed in three places, the first two being Helluland or “land of the flat stones” (possibly Baffin Island), and Markland or “land of forests” (possibly Labrador). Leif’s third landing was at a place he called Vinland, where he found grapes growing wild. Following Leif’s voyage, Norse groups attempted to colonise the new land, but the native people drove them out. Archaeological evidence of a Viking settlement was found in L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, which matches the description of Leif’s landing place in Vinland, except that grapes do not grow there today.

The European explorer acknowledged too as landing in what is now Canada was John Cabot, an Italian who was under the patronage of Henry VII of England. He sailed west from Bristol, England in an attempt to find a trade route to the Orient. He ended up landing on the coast of North America (probably Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island) in 1497 and claimed it for King Henry VII of England. Cabot was confident he had found a new seaway to Asia and, on a second voyage the following year, he explored and charted the east coast of North America from Baffin Island to Maryland. His voyages gave England a claim by right of discovery to an indefinite amount of area of eastern North America, specifically Newfoundland, Cape Breton and neighbouring regions. Of great significance were Cabot’s reports of immensely rich fishing waters.

The Roman Catholic countries of Western Europe furnished the fishing market, and every year after 1497 an international mixture of fishing vessels staked grounds off the southeast shore of Newfoundland and east of Nova Scotia. Sometimes these ships would traverse into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, encountering native peoples on the shore who would trade their valuable furs for trinkets and other items brought by the fishers. Nine fishing outposts on Labrador and Newfoundland showed the presence of Basque cod fishermen and whalers. The largest of these settlements was Red Bay. Basque whaling began in southern Labrador in mid-16th century. Fishermen from Brittany, Normandy and England joined Basque fishermen.

Be First to Comment